Life†

John of the Cross was born in 1542 in a small town in a rocky and barren part of Spain. His father had come from an upper-class family of silk merchants, but he married a woman of low estate for love, and he was disowned by his family. John was the third boy in this marriage, and at age 3 his father died. His wife, Catalina, with her three boys, struggled with unemployment and hunger.

When John was nine years old, Catalina succeeded in placing him in a school for poor children, but he wasn’t enthusiastic about the trades taught there. Instead, he discovered a gift of caring for the sick, and he worked as a nurse and alms seeker at a hospital in Medina.

While working at the hospital, he had an opportunity to attend evening classes in Latin and rhetoric at a local Jesuit school. He loved his studies there and excelled at them. When he was 21, the hospital administrator offered him ordination to the priesthood and a job as chaplain at the hospital. However, he decided instead to go into a Carmelite monastery.

After his novitiate, John attended university in Salamanca, where he excelled and eventually became an instructor. He was known for a sharp mind, knowledge of the Bible, the fathers, and theology, and an austere and contemplative life.

He apparently felt a draw to the contemplative life because he considered transferring to a more contemplative order, the Carthusians. However, he met St. Teresa of Avila, who was establishing a reformed version of the Carmelite order, the Discalced (or unshod) Carmelites, who returned to a more austere and strict observance including going barefoot. John decided to devote himself to this work. They followed a way called recollection, which made union with God through love its main concern, and had regard for authors such as Augustine, Bernard, and Gregory the Great. “This way of recollection, also called mental prayer, had to involve one’s whole life. You lived a life of recollection, a life of mental prayer.“

In addition to this movement of recollection, there was another at the same time, whose members followed a way called abandonment. They were more extreme, giving up vocal prayer for a kind of suspended state in God. They didn’t bother with fasts, meditation, rites, ceremonies, or the “religious life” in general, and they believed they were incapable of sin. They generated much suspicion and opposition, and the “Inquisition” was set up to coerce them into orthodoxy. Through the Inquisition, unrepentant “heretics” were tried and forced to convert or be burned at the stake. Moslems and Jews were also forced to convert to Christianity or leave Spain. (Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!)

Those who followed the way of recollection were often confused with those who followed the way of abandonment, and so they were also suspected and oppressed. And of course the traditional Carmelites weren’t pleased with those who wouldn’t wear shoes, perhaps feeling condemned for their warm toes and cool hearts. Some of them captured John and threw him into a monastery prison in Toledo. Imprisonment, flogging, and fasting on bread and water were standard penalties in religious orders at the time, and in John’s case they were severely applied in his small prison cell with only one tiny window, 2 inches wide and high above the floor. It was here that he composed some of his great poetry. Eventually he escaped and was hidden by some of his own order. Later he moved to a remote monastery in safe territory.

As with most or all prophets and saints, John was oppressed in life, and his teachings were controversial. Some loved them and others wanted them banned and burned. (And not just them, but him.) As, in fact, writings of people such as Augustine and Aquinas were burned. But eventually the writings were approved, then respected. He has since been named saint and “Doctor of the Church” by the Roman Catholics, where he is considered the leading writer and authority on the spiritual life.

Writings

John had an interesting relationship with scholarship and writing. Though he was brilliant and had taught at university, he left behind all desire for academic success and writing and knowledge. However, he wrote poetry on the spiritual life, and at the request of nuns he directed he wrote commentary on that poetry. He particularly wanted to address an aspect of the spiritual life that wasn’t much written about—the “dark night.” Actually, he wrote about two nights. The first is the “dark night of the soul,” which is common. It marks the progression from the “purgative” stage of the spiritual life to the “illuminative,” or from “novice” to “proficient.” The purgative state is characterized by sweetness in meditation and struggles to overcome sin. These are the beginners at contemplation who still have many faults and who still need the sweet milk of spiritual consolation. The dark night of the soul, which is relatively common, is a crisis that leads to the illuminative state, in which consolations are taken away and God’s spiritual presence is more clearly felt. Joy, tranquility, and illumination in spirit are more common, though there are also still times of absence and pain.

The second night is the “dark night of the spirit.” It is very rare, and it is much more intense and painful and fearful. It is the death of self, and it marks the transition from the illuminative to the “unitive” state, or from proficient to perfect. It results in some degree of continuous union with God in this life. In Catholic spirituality, maybe we can roughly identify people in this state with saints.

Each of these nights can be divided into an “active” and a “passive” component. The active part is that which we ourselves do with God’s help to reform ourselves, and the passive part happens to us without our effort, though with our consent. The struggle to overcome the passions—that’s the active night. Being thrown into a prison of darkness and confusion and doubt—in which love of God blossoms—that’s the passive night.

John wrote four major works as well as some poetry, maxims, and letters, and diagrams. (Most of his letters were burned to protect him and the monks and nuns to whom his letters were written when the Inquisition was investigating him.) The first two works were really intended to be a single work, a commentary on a poem he wrote in prison in Toledo. The commentary on the poem as it pertains to the active night is in a book also called The Ascent of Mount Carmel, and the part pertaining to the passive night (of sense and of spirit) is in a book called The Dark Night. Neither book was finished, but the parts that were written are considered great treasures of the spiritual life.

John’s other two major works are on a degree of the spiritual life rarely written about—the life in union with God. They take the form of commentary on poems. The first is The Spiritual Canticle and the second is The Living Flame of Love. The Spiritual Canticle has the feel of a retelling of the story in the Song of Solomon. The Living Flame of Love “marvels at the wood converted into a fire that continues to grow hotter, bursting frequently into lifelike flames.”

The Ascent of Mount Carmel

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is a book on the active dark night, in the form of a commentary on a poem. It describes the road up Mount Carmel, that is, union with God, and the effort on our part that is needed. Of course, one cannot attain union with God in one’s own strength, or even desire it—we “work out our salvation with fear and trembling,” only later understanding fully that “it is God who works in us.” So The Ascent covers the human effort which we later discover was God’s work all along.

As a book on the apparent human efforts required along the path, it describes a bunch of self-denial and renunciation that can be intimidating and off-putting. John describes the path all the way to the summit of the mount, and it is the road of faith, love, and hope in God alone, with self-denial and taking up the cross and rejection of all other desires, consolation, satisfaction, or revelation—self-denial that may be too extreme for many beginners to accept. When climbing a mountain, it’s generally a good thing that you can only see a little of the path ahead of you, not the whole path all at once. Maybe the best way to take this work is to take as much of it as you are able at the moment and not to worry about the rest, for God leads us gradually and gently up these long, steep slopes.

Keep in mind too that the work was written for nuns who had already dedicated their lives to serving God. As such, it addresses those who have already submitted to God and committed to attempting the journey. It deals with the purification needed along the way—the dark night. If you are not yet completely committed, this work likely won’t appeal to you at all.

Here is the first stanza of the poem:

One dark night,

Fired with Love’s urgent longings,

—Ah, the sheer grace!—

I went out unseen,

My house being now all stilled.

This stanza describes the dark night of purification, considered first as it pertains to the active night of sense. On a dark night (without clear understanding, in faith alone), moved by urgent love of God, the soul departed sensory appetites and imperfections—in a house in which all desires outside of God are quieted and tamed.

This departure is called night to signify the deprivation of the gratification of the soul’s appetites in all things. Just as night is a deprivation of light, the dark night of sense is a deprivation of the gratification of the appetites. When all foreign loves are gone, there is room to love God with the whole heart.

John calls this road the road of faith because it rejects the desire for clear knowledge, relying on faith. It rejects consolation, preferring to suffer for God. It rejects voices and visions and revelation, relying on the faith of scripture and the church. It rejects the love of the things of the world, instead loving God.

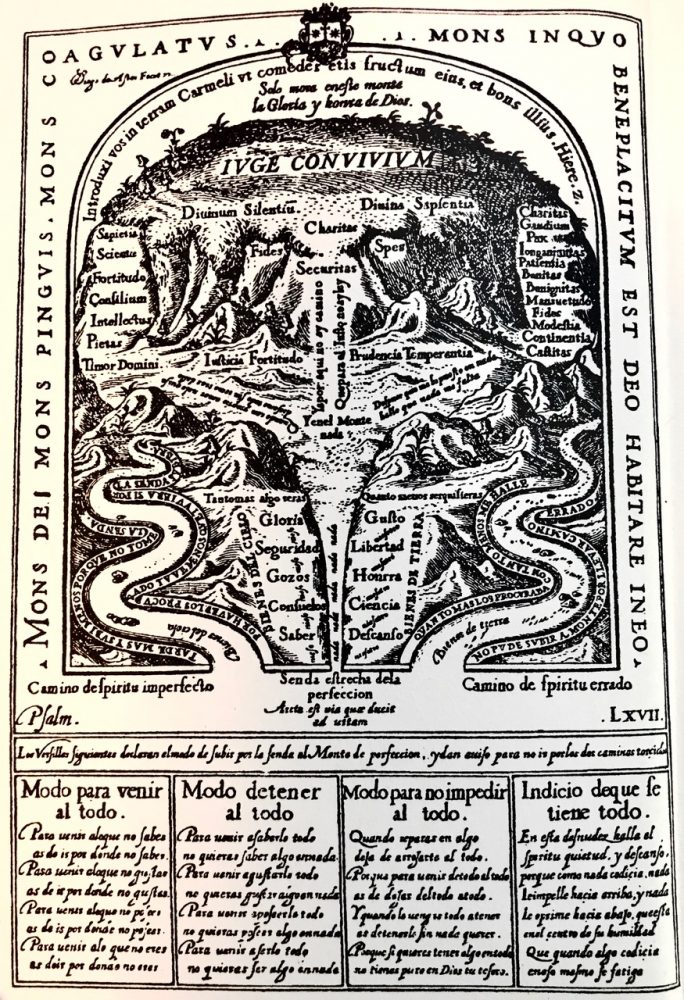

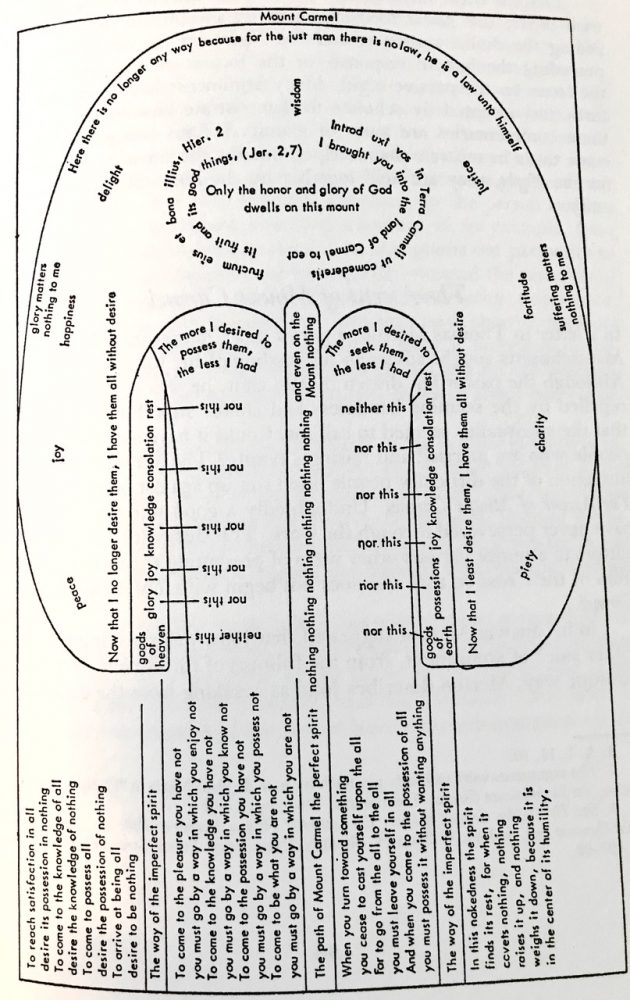

Since John lived before the era of the printing press, books were expensive and rare, so he often drew a diagram outlining the road of faith for people he directed, summarizing the way of faith. Here’s a aversion of the diagram and a translation of (a slightly different version of) the diagram:

Note that there are wide, easy ways up the sides of the mountain, the way of the imperfect (on the left) and the wrong path (on the right). They don’t go as high on the mountain, and they get narrower the higher you get. The left one involves goods of heaven: glory, joy, knowledge, consolation, rest. The one on the right involves goods of the earth: possessions, joy, knowledge, consolation, rest. The central path is narrow and rocky and steep and hard to follow, at least at first. It is the fastest and most direct way up the mountain, and it broadens after a little while. It involves “nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing” — no glory, joy, knowledge, or consolation. Only faith. Up on the mountain only the honor and glory of God exist. Wisdom leads to the very top of the mountain, where there is no longer a path — “for the just man there is no law, he is a law unto himself.”

The text at the bottom summarizes the road—don’t desire satisfaction, knowledge, possessions, or reputation. Desire God only. Go by a way without pleasure, knowledge, possessions, or self-regard. Turn away from the world and toward the all. Covet nothing. Do not be raised up or weighted down. Find your center in humility.

In summary, people following this road of active purgation must:

- not desire things like wealth, reputation, possessions, power

- set aside their own knowledge and walk in God’s service like uneducated children

- not be attached to the beauty of any created thing

- be purged of attachments to created things

- walk by faith

They must do three things:

- cast out strange gods (alien attachments or affections)

- deny these affections, repent of them, and purify themselves of the residue

- change their garments—be clothed in a new will, a new love of God above all

Nothing can dwell together with God in the affections. It is necessary to have freedom from all appetites. In short, we must love God with the whole heart and mind and soul and strength.

John gives guidance to enter this night of sense:

- Have a habitual desire to imitate Christ. Study his life. Bring yours into conformity.

- Renounce and remain empty from any sensory satisfaction that is not for God’s honor and glory.

- Mortify and pacify the passions. That is, endeavor to be inclined always:

- not to the easiest but to the most difficult

- not to the most delightful but to the harshest

- not to the most gratifying but to the less pleasant

- not to what means rest for you, but to hard work

- not to the consoling, but to the unconsoling

- not to the most, but to the least

- not to the highest and most precious, but to the lowest and most despised

- not to wanting something but to wanting nothing

- not to the best of temporal things, but to the worst

- Embrace these practices and try to overcome the repugnance of the will you will feel. If you put them into practice, you will feel in them great delight and consolation

At this point (if not before) many readers put down the book and figure it’s not for them, it’s too hard, too extreme, too unreasonable. But notice that the advice is to “endeavor,” not to achieve. My advice would be to think incrementally. Is there any progress you can make, without worrying about the whole journey all at once? Can you study the life of Christ? Is there something you can give up or add to your life? Are there exercises you can do to gain control over the passions, such as fasting? The next time you make a difficult decision, can you choose what is unattractive to the flesh but what God would have you do? Then again, maybe this is bad advice. Paul advises us to run the race intending to win.

This is all rather a lot to hold in your mind all the time. Can you memorize and meditate on a little summary aphorism, such as this, then repeat it in your mind frequently?

Desire enjoyment in nothing,

Nor knowing nor having nor being,

To come to enjoyment in all things,

To living and loving and seeing.

Of course, we are unable to accomplish all this in our own strength. We need God’s help, and, ultimately, we need God to further and finish the work, which he does in the dark nights, described in his next major work, The Dark Night.

The Dark Night

The Dark Night is a continuation of the Ascent of Mount Carmel, dealing with the passive aspects of the two dark nights a soul may pass through on the road up Mount Carmel, that is, the aspects of purgation that God performs in us without our own effort. It again considers the same first stanza of the poem, but this time as it pertains to passive purgation. The dark night is faith. At first it is experienced as a lack of clear knowledge or consolation—darkness. Later, the soul discovers that this very darkness or lack is a transition to a deeper, more direct knowledge of God.

Dark night of sense

The dark night of sense is a purgation of the senses. This night is relatively common and happens to many. It results in a quelling and diminution of the desires of sense for the things of this world and a growth in spiritual purity of love of God. It may present a spiritual depression, with depressed desires for the things the soul previously loved. There may be little interest in socializing, eating, watching TV, shopping, following the news, acquiring possessions, getting ahead, whatever kinds of desires and employments the soul was accustomed to. Even the enjoyable things of the faith are not exempt: there may be no enjoyment in going to church or singing or praying or meditating. There may be an inability to meditate or pray. It may seem as though the soul is losing its faith or is abandoned by God. And yet, though all else may be taken away, the yearning for God is still there, in a dark and confused and possibly hidden way.

Some of these symptoms are similar to normal depression, so John give three signs for determining whether a soul is in the night of sense:

- They do not get satisfaction or consolation from the things of God or from the things of the world (dryness in the affections)

- They fear they are not serving God but turning back, because they are aware of a distaste for the things of God

- They are powerless to meditate or pray using reason and the senses, as they previously did

Prior to this dark night, much of the spirituality of these souls was in the senses: seeking deep thoughts and warm feelings and other rewards in meditation and prayer and service. This is a very selfish and carnal way of serving God, so this purgation is necessary to enable further progress. God transfers his grace from sense (reason and feelings) to spirit, and sense feels deserted and abandoned, so it complains. This transformation therefore marks the transition from “servant of God,” who serves primarily for the rewards and good feelings received, to “friend of God,” who serves for love. Or perhaps it can be compared to Paul’s discussion of spiritual milk vs. solid food or from a carnal Christian to a spiritual one.

This purgation may occur after many years of dedicated Christian life, and it may last for weeks or months or years. Or, it may never occur. It may be comparable in intensity to a minor blue phase or a severe depression. It all depends on God’s foreknowledge and call of each person.

This new activity of God’s grace in the spirit is the beginning of contemplation, and this dark night marks the transition from beginner to progressive, from the purgative way to the illuminative. People in the latter state tend to move back and forth between sweetness and dryness, dark clouds and bright light, confusion and clarity, dejection and love. People in this state who can no longer meditate should not give up but feel comforted; they ought to persevere patiently, for now they are on a different road. They should allow the soul to remain in rest and quietude, even though it may seem obvious to them that they are doing nothing and wasting time, for at the beginning, this contemplation may be hidden even from the one experiencing it. But if they persevere, they will eventually realize that this “contemplation is nothing else than a secret and peaceful and loving inflow of God, which, if not hampered, fires the soul in the spirit of love.”

Dark night of spirit

According to John, after many years on the illuminative way, after much progress and deepening and change, a soul may eventually enter a second night, the dark night of spirit. This night is much more fearsome and terrible than the other, and it is very rare. In the first night, sense was restrained; in this night selfish sense and spirit are torn out by the roots. The soul dies to self completely and is reborn in Christ. This night marks the transition from the illuminative way to the unitive, or from the state of the proficient to the state of perfection. (Perhaps “perfection” is a misleading state name to use here because no one in this life is perfect, and temptation and progress still take place.)

Before the dark night of spirit, “these proficients are still very lowly and natural in their communion with God and in their activity directed toward Him because the gold of the spirit is not purified and illumined. They still think of God and speak of Him as little children, and their knowledge and experience of Him is like that of little children. . . . The reason is that they have not reached perfection, which is union of the soul with God. Through this union, as full-grown persons, they do mighty works in their spirit, since their faculties and works are more divine than human. . . . Wishing to strip them in fact of this old man and clothe them with the new, . . . God divests the faculties, affections, and senses, both spiritual and sensory, interior and exterior. He leaves the intellect in darkness, the will in aridity, the memory in emptiness, and the affections in supreme affliction, bitterness, and anguish, by depriving the soul of the feeling and satisfaction it previously obtained from spiritual blessings. For this privation is one of the conditions required that the spiritual form, which is the union of love, may be introduced into the spirit and united with it. The Lord works all of this in the soul by means of a pure and dark contemplation” (p. 199).

“Souls suffer affliction in [this] manner because of their natural, moral, and spiritual weakness. Since this divine contemplation assails them somewhat forcibly in order to subdue and strengthen their soul, they suffer so much in their weakness that they almost die, particularly at times when the light is more powerful. Both the sense and the spirit, as though under an immense and dark load, undergo such agony and pain that the soul would consider death a relief. The prophet Job, having experience this, declared: I do not want Him to commune with me with much strength that He might not overwhelm me with the weight of His greatness [Job 23:6].” (p. 202-3).

John’s Spirituality

- The narrow path is the “way of faith”: not through consolation, sweet feelings, and rewards, but through darkness, dryness and suffering.

- In short: love God purely. Reject other desires, including those for good feelings in prayer and meditation or rewards for service.

- Perfection is a state of union with God.

- Contemplation is a dark inflow of God’s love.

- To get there, you need to do all that you can and to pray for help. You can’t do it on your own, but it won’t happen without your total effort and the dedication of your whole life.

- Self-denial is needed to overcome the desires of the flesh.

- Taking up the cross (patience in suffering) is necessary, as there will be much suffering. In fact, you will come to desire the suffering that is the death of self and the participation in Christ’s redemption of the world.

- Spiritual direction is needed.

- The short route: deny yourself. When faced with a choice, always choose what God would have, what flesh doesn’t want. The short route is whole-hearted love and utter obedience.

Desire enjoyment in nothing,

Nor knowing nor having nor being,

To come to enjoyment in all things,

To living and loving and seeing.

†Much of this discussion summarizes and at times quotes the introduction and text of John of the Cross: Selected Writings, ed. Kieren Kavanaugh, Paulist Press, 1987.