Read Isaiah 64:1-9.

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence—as when the fire kindles brushwood and the fire causes water to boil—to make your name known to your adversaries, so that the nations might tremble at your presence! (Isaiah 64:1-2)

Apparently Isaiah wasn’t very good at prayer, or maybe he wasn’t righteous enough, or he didn’t have enough faith—there is no record of a tear in the heavens through which God came down to cause earthquake and wildfire and fear.

Or maybe that wasn’t Isaiah’s actual intent. Maybe he is pouring out his heart, expressing his desires, the desires of the people, not actually demanding that God rend the heavens, shake the mountains, and terrify the nations.

It seems to me that there are at least three modes of prayer that may be broadly categorized as petition. In the first we pour out our hearts to God. We show our desires without actually asking that they be granted. We express them, and by doing so, we reveal ourselves. Sometimes it’s not pretty, but when we air our desires they are purified. Maybe the imprecatory psalms have this character.

Lord, save. Lord, come quickly. Lord, banish evil and hunger and war and injustice. Lord, stop that evil person. Lord, pay back my oppressors what they deserve. Lord, heal this sickness. Lord, where is your justice! Lord, help me find my car keys. I don’t actually expect evil to end tomorrow, nor am I expecting my keys to miraculously appear on the countertop. I’m expressing my desires.

This kind of prayer is really as much communion as petition. By it, my will scrapes against God’s will and loses its rough edges. Our wills twist together and become one.

The second mode of petitionary prayer is a deliberate and intent request. In it we ask that God act, and we expect a result. We pray persistently and passionately. Maybe we make the request explicit somehow, perhaps by asking the church to pray and to anoint with oil. We have faith that our request will be granted, or maybe something even better.

To express a desire and to solemnly ask are not the same thing. The latter has more intention and expectation. In my experience the former is common and the latter less frequent.

The third mode of petitionary prayer is the prayer of power. In it we pray in union with God’s will. We pray in Jesus’ name—we pray in his place and with his authority. We command that it be done. We instruct the demon to leave, the illness to be healed.

Or maybe these are differences of degree rather than mode. Maybe they can be expressed as parameters of petition:

- Motive—why do you ask? Are you asking for selfish reasons, or are you moved by love?

- Intent—are you explicitly asking for an outcome or are you really just expressing a desire?

- Vehemence—are you demanding and persistent, or are you abandoned to whatever God thinks best?

- Expectation—are you praying in faith? Do you actually believe that the person with cancer will be healed or that war will cease and justice prevail?

- Union—are you praying for what you know to be God’s will, so that together you see that it is good and desire it fervently and command that it be done?

Meister Eckhart says:

The most powerful prayer and almost the strongest of all to obtain everything, and the most honorable of all works, is that which proceeds from an empty spirit. The emptier the spirit, the more is the prayer and the work mighty, worthy, profitable, praiseworthy, and perfect. The empty spirit can do everything.

And what is an empty spirit?

An empty spirit is one that is confused by nothing, attached to nothing, has not attached its best to any fixed way of acting, and has no concern whatever in anything for its own gain, for it is all sunk deep down into God’s dearest will and has forsaken its own. A man can never perform any work, however humble, without it gaining strength and power from this.

We ought to pray so powerfully that we should like to put our every member and strength, our two eyes and ears, mouth, heart, and all our senses to work; and we should not give up until we find that we wish to be one with him who is present to us and whom we entreat, namely God.*

Does Meister Eckhart really say that the detached person no longer prays petitionary prayers? On the contrary, such a one prays vehement and powerful petitions in union with God.

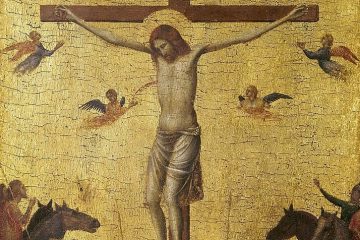

Then again, maybe the heavens were rent and God did come down, just not in the way the words at first blush seem to suggest. O come, O come Emmanuel!

——

*Meister Eckhart, Paulist Press, 1981, p.

See also Meister Eckhart’s Sermons, containing seven of his sermons, and other volumes of works by Eckhart at CCEL.