The Apostle’s Creed states the fundamental beliefs of the faith: “I believe in God the Father. . . He was raised again from the dead. . . I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.” While growing up I recited this in church each week. This “Apostle’s Creed” was first referred to by that name in A.D. 390, though it wasn’t written in final form until around A.D. 710.

Most of the statements are fundamental tenets of the faith, beliefs that are essential to the faith, claims that may be hard to believe apart from revelation and divine inspiration. And then there is the statement, “I believe…in the communion of the saints.”

What is so hard to believe about the communion of the saints, and why is it so essential to the faith? I myself have seen them chatting together after church, maybe even going to a church potluck.

OK, maybe that’s not all that the framers of the Apostle’s Creed had in mind. Apparently there is something special, something fundamentally important, something astonishing about what is referred to in the creed as “the communion of the saints.” What is it?

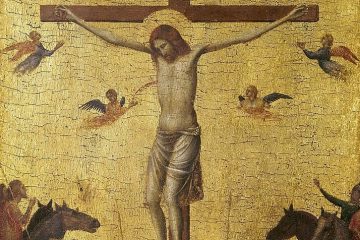

What to do with theological questions? That’s right, head over to Wikipedia. There “communion of the saints” is defined as the mystical union experienced by members of the church, both living and dead. The communion of the saints is Christ’s body.

We are united with God in love. As we love God above all, as we give ourselves to him, so he gives himself to us. We become one spirit. We love what God loves and desire what he desires.

Christ expressed his love by emptying himself and becoming a servant. As we Christians follow him, as we empty ourselves and wash the feet of our brothers and sisters, as we give ourselves to our brothers and sisters, and they to us, we become one spirit. We experience the communion of the saints.

Thomas Kelly’s little classic A Testament of Devotion has only five chapters on the spiritual life, on the light within, holy obedience, the blessed community, social concern, and the simplification of life. Fully one of these five chapters is devoted to the “blessed community,” or the communion of the saints, of which he speaks profoundly and at length.

Kelly writes, “’See how these Christians love one another’ might well have been a spontaneous exclamation in the days of the apostles. The Holy Fellowship, the Blessed Community has always astonished those who stood without it. The sharing of physical goods in the primitive church is only an outcropping of a profoundly deeper sharing of a Life, the base and center of which is obscured, to those who are still oriented about self, rather than about God. . . . But every period of profound re-discovery of God’s joyous immediacy is a period of emergence of this amazing group inter-knittedness of God-enthralled men and women who know one another in Him. . . . Yet still more astonishing is the Holy Fellowship, the Blessed Community, to those who are within it. Yet can one be surprised by being at home? In wonder and awe we find ourselves already interknit within unofficial groups of kindred souls.”

Do you want to join this blessed community, this body of Christ? You must first give yourself to God without reserve. Then, in him, give yourself to everyone. Empty yourself and become a servant.