Calvin identifies holiness and consecration as the goals of the Christian life, but he doesn’t say much about how to get there or the process of transformation, apart from advice to take up the cross, to have patience in suffering, and to live moderately. But of course these things are hard or impossible to achieve perfectly through main force of will. How do I get there?

Are there concrete steps I should take, ends I should strive for, or does God do everything for me? Should I be motivated by fear, or by love, or by some combination of the two? Should I govern my behavior by careful watching to avoid sin, or by freedom in Christ? Should I pray continuously by repeating a set prayer many times, or by praying extemporaneous mental prayers at all times, or by mindfulness of God? Should my inner life be dominated by contrition, or by humility, or by gratitude, or by love and joy? Should I deny myself by fasting, staying awake, and praying? Should I meditate on sacred writings or seek the stillness in which God may be known? Is the goal dispassion, or detachment, or recollection, or stillness, or abiding in Christ, or loving God and neighbor? Or should there by no system at all, but a simple will to follow the leading of the Spirit?

There are many paths and methods of Christian spirituality. I suspect that each has its own genius, and each its own distinct glory in the resurrection. One such path leads to the desert.

In the early centuries of the church, perhaps in reaction to Christianity becoming official and political (and tepid?) in Rome, some Christians set off to the desert, perhaps in Egypt, to train with all their might to become good Christians, like athletes training for the Olympics. There were two main forms of this life. The first was a life in community and in obedience to an abba. The second was a life of solitude and in stillness. Many great saints grew up in this environment. Some of their sayings are recorded in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

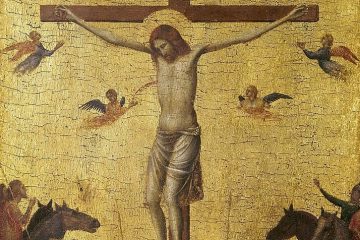

Perhaps the most important and commonly used “training guide” of that era for this form of spirituality is The Ladder of Divine Ascent by John Climacus.* It is largely an ascetic work, describing many deadly passions and vices to eradicate, many virtues to acquire, and many practices for getting there. The path is modeled as a ladder with thirty steps, each a vice to eliminate or a virtue to acquire. The last four steps, on stillness, prayer, dispassion, and love, are more contemplative in nature.

The goals of this form of spirituality are stillness and dispassion. Stillness is cessation of striving and prayer without ceasing. Stillness is the single eye. Stillness is guarding the mind and overcoming temptation and distraction. Stillness starts with aversion to noise and ends with immunity to it. Stillness starts in the closet and ends in the public square. One who practices stillness is “rarely moved to speech and never to anger.” Stillness is the peace that surpasses understanding. In stillness, words, images, and desires end and God himself may be known.

Dispassion is the overcoming of sinful passions such as anger, malice, gluttony, lust, avarice, fear, despondency, vainglory, and pride. “A man is truly dispassionate . . . when he has cleansed the flesh of all corruption; when he has lifted his mind above everything created; . . . when he keeps his mind continuously in the presence of the Lord.” “Dispassion is the uncompleted perfection of the perfect.” “The dispassionate man no longer lives himself; but it it Christ who lives in him.”

There is in The Ladder a progression from human effort to divine gift. But most of the work is on the first part, the struggle against the passions. To that end, The Ladder recommends many training exercises, including eating one meal a day (and not stuffing yourself), staying awake all night in prayer, remembering death, mourning sin, singing the psalms, unquestioning obedience, drinking as little water as possible, and more. But one of the more characteristic practices is to have the name of Jesus on your lips at all times. The practice of the Jesus prayer was not fully developed in The Ladder, but it is an important part of that tradition. It is to pray the Jesus prayer, “Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” or some shorter variant, or some other short prayer, often, regularly, continuously. Though the prayer starts out on the lips, in time, mental prayer, the affections, stillness, will follow.

*Tr. Luibheid and Russell, Paulist Press, 1982. The only public domain English translation, or really more of a paraphrase, is The Holy Ladder of Perfection, by which we may ascend to heaven, by Father Robert, Monk of Mount St. Bernard’s Abbey (Leicestershire, England), London, 1858.

See also: The Way of a Pilgrim, a charming little narrative about a nineteenth century Russian peasant who starts out trying to learn how to follow the biblical injunction to pray continuously. The story tells of his travels, his learning to pray the Jesus prayer, and its effects.