Read Matthew 4:1-11.

There are a number of traditional exercises intended to help us “crucify the flesh” or gain mastery over the passions, such as watching and praying, guarding the heart, meditating on Christ’s passion, meditating on scripture, discussing our spiritual state with others, and keeping silence. One of the most common is fasting. It is practiced in all major religions.

When we abstain from eating, well, we get hungry. We feel pain. We get light headed. Maybe we get hangry. This is an ideal opportunity to practice spirituality. Notice the feeling of hunger. Notice the pain. It’s bearable. Now consider that you have a choice of whether to eat or not. You are in control, not your feelings. You won’t die if you don’t eat for a while longer. Exercise your control and embrace the pain. Scorn the passion.

“Scorn the passion” sounds too active. Be at peace. You notice the hunger without letting it upset you, without letting it get to the level of your will. You notice the hunger, a little, and then gently turn your attention away from it. To God. Maybe you train yourself to let the desire for food remind you of your desire for God. With every pang of hunger, you pray.

You practice fasting to learn that you don’t have to be controlled by your passions. You fast to learn how to deal with passions and overcome them. You fast to help yourself watch and pray. Fasting is not itself a good deed or moral virtue, it’s just an exercise, usually temporary or episodic. When you fail, ask for help and begin again the next day.

But there is more to fasting than mortifying the flesh. Moses fasted on Mt. Sinai for forty days and nights in the fiery cloud of God’s presence, receiving the law. Elijah fasted for forty days and nights after calling for a drought, raising the widow’s son from the dead, calling down fire from heaven on Mount Carmel, slaughtering the priests of Baal, and escaping into the wilderness. Esther, along with all the people, fasted to prepare for her to speak to the king about saving the people. Joel called for a corporate fast in the face of a plague of locusts. In Acts the leaders of the church fasted before choosing missionaries and elders. Fasting can express grief or penitence. It is a way to humble oneself or to gain a hearing from God or to know God’s will.

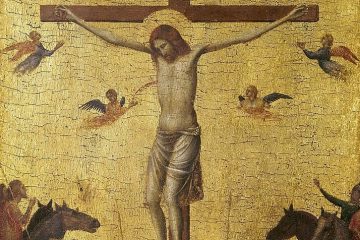

And, of course, the Spirit led Jesus into the wilderness for forty days, where he was tested, in preparation for his public ministry. This is the fast we remember primarily during Lent.

Calvin, and St. Peter of Damascus, call for moderation in fasting. Peter claims that too much eating and too much fasting can both bring about undue pleasure (!). Peter says that we should fast moderately: eat one meal a day, preferably of just one kind of food that we are not particularly fond of each day, stopping before we are full (!!).

Is the Spirit perhaps leading you this Lent to follow Jesus into the wilderness, to enter into a time of solitude, fasting, testing, and preparation?