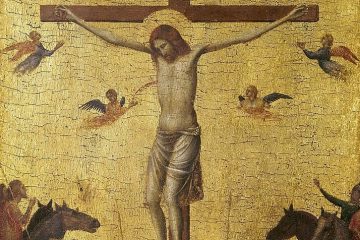

In the 14th century, when Ruysbroeck lived, there was no doubt a great deal of illiteracy, especially if that is understood to mean the inability to read and write Latin, the language of the church. Therefore images and rituals were a significant component in worship. Churches had stained glass windows and frescoes and paintings and sculpture. Worshipers might meditate on sculptures or paintings representing the stations of the cross, perhaps, imagining each station, pondering its implications, placing themselves in the situation, and the like. So when Ruysbroek says that a spiritual life requires worship without images, perhaps the first thing that would have come to a reader’s mind is that worship has to go beyond meditation. Meditation on the cross of Christ can be useful in bringing us closer to God, but these mental images are not God. To meet God is not to have mental images of him.

Speculative reasoning falls into the category of “images” as well. Concepts we have of God, theological formulations, even descriptions of attributes of God such as omniscience, omnipotence, omnipresence, simplicity, triunity, or love, all are images of God. All are concepts or imaginations that fall short of God Himself. Worship in spirit rises above imagining God into loving him and meeting him.

Ruysbroeck goes on to say that “In his exercises a person should make good use of images, such as our Lord’s passion and anything else which can stir a person to greater devotion; in possessing God, however, a person must descend into that imageless bareness which is God himself.”

What does it mean to “descend into imageless bareness”? Reason is quiet—you aren’t trying to figure something out or learn something or find an answer to a question. Memory is quiet—you put the past out of mind. Affections for the world are quiet—you leave cares and concerns outside your room. Fear is quiet—you have abandoned yourself to God’s care. Shame is quiet—you don’t think about yourself at all. Desires are quiet—you have entrusted yourself to God’s care, asking for nothing. You relax. You are at peace. And in this peace, you seek God. You desire him. You offer yourself to him. You meet him. This is not a meeting of intellects for discussion over a cup of coffee, it is a tryst in the dark. You are confused, in a cloud, unable to see, but you love and are loved. And as the darkness grows, eventually you may be able to make out the pillar of fire.

To me it seems that Ruysbroek’s language of “descending into imageless bareness” describes a change in location of worship, from the intellect to the affections, from words to desires, from images to intense love. We love God with heart and soul and mind and strength. We give ourselves to him, and he himself to us.

Do you desire not to know about God, but to know God? Do you desire to worship in spirit? Pray for love, pray for guidance, seek him above all else, and God will lead you along the path of knowledge. Normally this path goes primarly through meditation and prayer. Don’t be surprised, though, if some day you find yourself unable to meditate or to pray. You have surrendered yourself, you live for him, you love him, but you are unable to meditate. You have no clear concepts or images. You are confused. All you have is love and desire. You have entered the cloud. You have “descended into that imageless bareness which is God himself.” Seek God not in images and reasoning and acts of will but in love and in presence. This is the entrance to the spiritual life.

Image: The Crowning with Thorns, Anthony Van Dyck