Dear Hazelnuts,

Thanks for the good discussions last Sunday!

We spent much of the time talking about Julian’s statements that “God does all that is done,” “all that is done is well done,” and “sin is no deed.” Julian’s obviously not a Calvinist, but she certainly had a high view of providence, of God’s role in all that happens. One of the more radical things she says is that “all that is done is well done.” According to Julian, someday we will look back and see that all of the apparently evil things that happened in the world worked together for good, and we will rejoice.

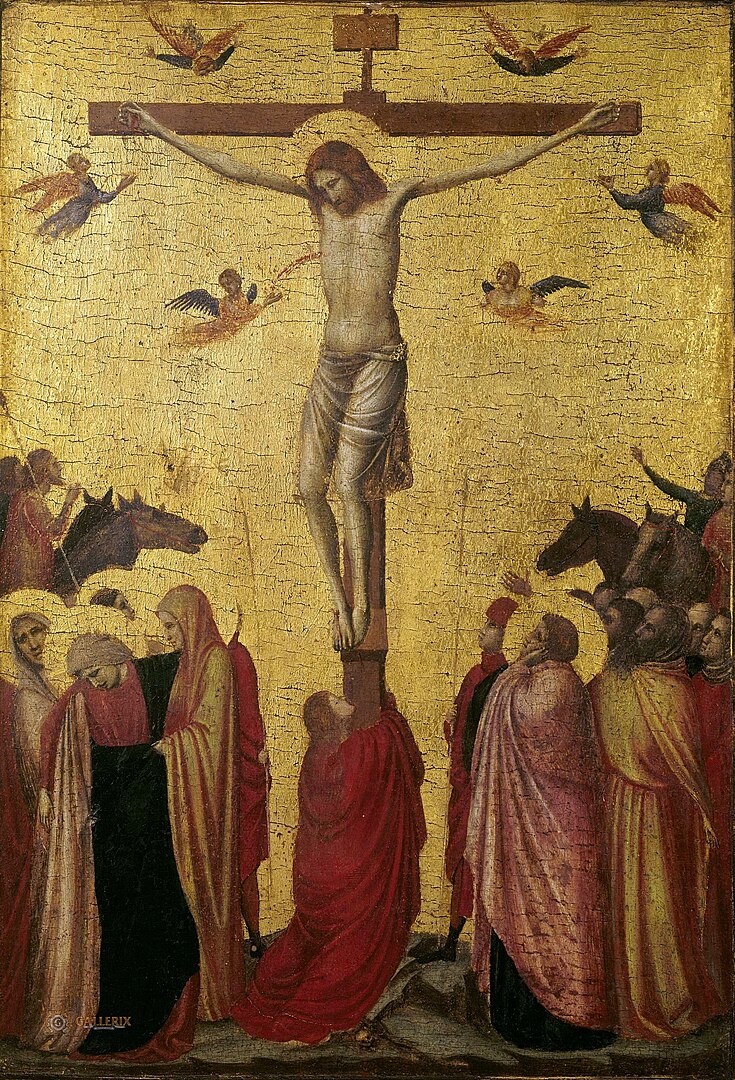

Another topic that came up was Julian’s emphasis on blood. What’s that all about? Is it just a symbol of Jesus’ self-giving love for us, or does it have some real power, like wine transubstantiated into Jesus' blood? In fact, a number of the revelations are graphic if not gruesome—revelations of the blood pouring down Jesus’ face, of his bones disjointed, of his skin drying and becoming detached, and the like. What kind of spirituality meditates on such things?

To get at this question, let me ask you another one. What do you seek in prayer or devotional practices? What is your goal? Sure, you ask God for something. But how is that process supposed to change you? And into what?

The contemplative spirituality of the medieval era sought to follow a road toward union with Christ. In this union, Christ and the Christian become united in will — they love the same things and hate the same things. They become united in knowledge—God teaches them and reminds them of all things. They become united in love — the Christian loves God above all and neighbor as self; God loves them and gives himself to them. Maybe someday they too will be able to say, “to live is Christ, to die is gain.”

This road was primarily affective—primarily via growing love. We seek to love God above all. And the way to grow in love was primarily by meditating on Jesus’ life, and especially his passion. We ponder God’s love for us, we see and even experience his suffering love for us, and our love for him grows in return.

George Maloney S.J. puts it this way:

Whatever is of prime importance in the various kinds of spirituality that came to flower in the second half of the fourteenth century across the face of Western Europe is here, whether it is labeled Carthusian, Cistercian, Dionysian, Franciscan piety, or “Modern Devotion.” . . . For all of them there is no other way to the summit of unitive contemplation than affective meditation on the suffering humanity of Christ: “That is,” writes Thomas of St. Victor, “in careful consideration of the blessed, beautiful, wounded Christ. For among all the exercises of the ascent of the spiritual intelligence, this is the most efficacious. Indeed, the more ardent we are in his sweet love, through the devout and blessed imaginative gazing on him, the higher we shall ascend in the apprehension of the things of the Godhead.” . . . The true test of the soul’s advance in virtue, of her growth in the divine likeness, is her imitation of Christ who loved us first and left us an example.*

Meditations on the blood, the thorns, the sufferings of Christ were intended to increase her love of Christ and to make her more like Christ. Julian says she already had some compassion for Jesus’ suffering. She prayed for deeper compassion, she gained deep insight into God’s love for us, and she grew greatly in love of God and in knowledge of God’s love.

For us enlightened modern people, meditations designed to raise the affections may seem foreign or off-putting. But is it really possible to grow in grace without growing in love? If we take the cross out of Christianity, what’s left?

This week we’re reading chapters 15-21 and next week 22-28. There are definitely some bloody meditations. All you have to do is to let yourself think about what Christ suffered for you. Chapter 27 has the famous line, “Sin was necessary, but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Blessings,

Harry

The Pursuit of Wisdom, ed. George Maloney, Paulist Press, 1988, pp. 189-190.