[This is an email sent to the group discussing Julian's Revelations of Divine Love]

Dear Hazelnuts,

(Sorry. But I need a collective noun for participants in this group. You’ve all been created by God, and God loves you, and God preserves you, right? And some of you are a little nutty? OK, maybe just me.)

Thanks for meeting last Sunday. I enjoyed it. If you have any suggestions for how the group might run better or things you’d like to discuss, let me know.

One person asked for an edition of the book with larger print. I have two suggestions:

- Read the online edition, and make the text larger. Caveat: this edition is a mild updating of the Middle English, so it’s harder to unerstand. On the plus side, it’s very close to the original.

- Buy or borrow a different edition that has bigger print. The Paulist Press edition (eds Colledge, Walsh, and Leclerq) has print that is quite a bit bigger and bolder. It’s more expensive, but used copies are available.

One thing we discussed is Julian's vision of a hand holding a ball as small as a hazelnut. She perceived that it represented all that has been created. She was shocked by its small size--she wondered how it didn't fall apart. But then she understood that God created it, God loves it, and God preserves it.

Thank you Marcia for bringing the hazelnuts! I put mine in my pocket. Yesterday, whenever I put my hand in my pocket, I felt it, and I thought “God created it, God loves it, and God preserves it.” Then I thought about that in connection to my current problem, or the person I was interacting with, or the part of the world I was looking at. Interesting experiment.

Another thing we talked about was what kind of spirituality would live in strict enclosure, foregoing many of the pleasures of the world, spending life in prayer and service? What kind of spirituality would pray for suffering?

I gave my opinion that it is not a kind of nature-grace dualism, where earth, nature, is neutral at best, but we should all be striving for heaven. So we should eat as little as possible, not marry or have a family, escape this world as much as possible.

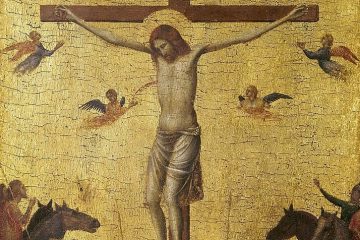

Rather, it is a spirituality of the imitation of Christ. Christ emptied himself and became a servant, so we should do that as well. Christ was poor; we should be poor. Christ suffered; we should expect suffering. We should become like him in all things.

I am going to append a chapter of a book called The Imitation of Christ, written at nearly the same time over in the Netherlands by Thomas à Kempis. This whole book exemplifies that spirituality, and this chapter in particular talks about suffering. (Sorry about the masculine pronouns...)

Few Love the Cross of Jesus

JESUS has always many who love His heavenly kingdom, but few who bear His cross. He has many who desire consolation, but few who care for trial. He finds many to share His table, but few to take part in His fasting. All desire to be happy with Him; few wish to suffer anything for Him. Many follow Him to the breaking of bread, but few to the drinking of the chalice of His passion. Many revere His miracles; few approach the shame of the Cross. Many love Him as long as they encounter no hardship; many praise and bless Him as long as they receive some comfort from Him. But if Jesus hides Himself and leaves them for a while, they fall either into complaints or into deep dejection. Those, on the contrary, who love Him for His own sake and not for any comfort of their own, bless Him in all trial and anguish of heart as well as in the bliss of consolation. Even if He should never give them consolation, yet they would continue to praise Him and wish always to give Him thanks. What power there is in pure love for Jesus—love that is free from all self-interest and self-love!

Do not those who always seek consolation deserve to be called mercenaries? Do not those who always think of their own profit and gain prove that they love themselves rather than Christ? Where can a man be found who desires to serve God for nothing? Rarely indeed is a man so spiritual as to strip himself of all things. And who shall find a man so truly poor in spirit as to be free from every creature? His value is like that of things brought from the most distant lands.

If a man give all his wealth, it is nothing; if he do great penance, it is little; if he gain all knowledge, he is still far afield; if he have great virtue and much ardent devotion, he still lacks a great deal, and especially, the one thing that is most necessary to him. What is this one thing? That leaving all, he forsake himself, completely renounce himself, and give up all private affections. Then, when he has done all that he knows ought to be done, let him consider it as nothing, let him make little of what may be considered great; let him in all honesty call himself an unprofitable servant. For truth itself has said: “When you shall have done all these things that are commanded you, say: ‘we are unprofitable servants.’”

Then he will be truly poor and stripped in spirit, and with the prophet may say: “I am alone and poor.” No one, however, is more wealthy than such a man; no one is more powerful, no one freer than he who knows how to leave all things and think of himself as the least of all.